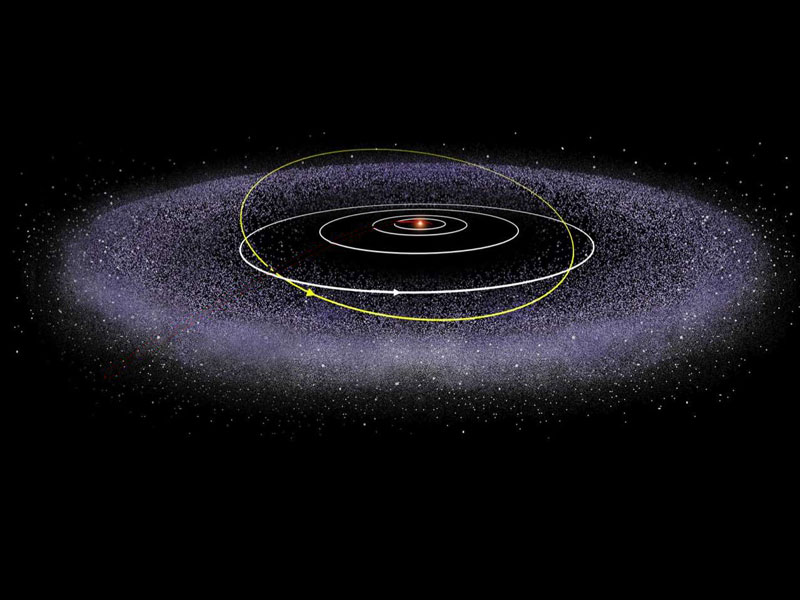

The Kuiper belt, also known as the Edgeworth–Kuiper belt, is a circumstellar disc in the outer Solar System, extending from the orbit of Neptune from the Sun. When the solar system formed, much of the gas, dust and rocks pulled together to form the sun and planets. The planets then swept most of the remaining debris into the sun or out of the solar system

The Kuiper belt was named after Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper, though he did not predict its existence. In 1992, Albion, the first Kuiper belt object (KBO) since Pluto and Charon, was discovered. Since its discovery, the number of known KBOs has increased to thousands, and more than 100,000 KBOs over 100 km (62 mi) in diameter are thought to exist. The Kuiper belt was initially thought to be the main repository for periodic comets, those with orbits lasting less than 200 years. Studies since the mid-1990s have shown that the belt is dynamically stable and that comets’ true place of origin is the scattered disc, a dynamically active zone created by the outward motion of Neptune 4.5 billion years ago; scattered disc objects such as Eris have extremely eccentric orbits that take them as far as 100 AU from the Sun.

The Kuiper belt was hypothesized in many ways for several decades. However, the first direct evidence for its existence was found in 1992. The hypothesis took many forms; however, the discovery of the Kuiper belt began with the study of comets. In 1987, astronomer David Jewitt, encouraged his then-graduate student Jane Luu to aid him in his attempt to locate objects beyond Pluto’s orbit. Finally, after five years of searching, Jewitt and Luu announced on August 30, 1992 the “Discovery of the candidate Kuiper belt object 1992 QB1” and six months later, they discovered a second object in the region. By 2018, over 2000 Kuiper belts objects had been discovered.

The masses, considered remains hailing from the formation of the Solar System, make up the belt; mirroring the similar relationship between the Jupiter and the main asteroid belt. Astronomers think that the Kuiper Belt vividly depicts the pathway of objects, meant to form a planet. However, Neptune’s gravity disrupted this region that coalition of those small icy bodies to form a large planet was not achieved. The Kuiper Belt lodges millions of small icy objects (dwarf planets, comets, moons and binaries), of varying colors, sizes and shapes, characterized as the Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) or trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) which are scattered throughout. Additionally, the existence of rock and water ice has been highlighted as well as the prevalence of a plethora of frozen compounds like ammonia and methane. The KBOs can be grouped according to their structure, characteristics and how the objects interacted with Neptune’s gravity. Pluto was the first KBO to be discovered and is tagged nowadays as the ‘King of the Kuiper Belt’, being the largest body in the region.

Surprisingly, it has only been a few decades since we have discovered the Kuiper belt. Therefore, the current methods of observing it are still limited, but evolving nonetheless.

The main method of studying the belt comes from telescopes around the Earth itself, most notably the Hubble Space telescope, and a more recent one is NASA’s space-mission ‘New Horizons’ with the launch of an interplanetary space probe. It continues to make significant contributions to studying this region and was the first of its kind to visit a foreign object within the region.

On board of the New Horizons are image sensors, spectrometers and a student-built ‘dust counter’ which are being used alongside grounded telescopes. Data from the probe and Earth telescopes do not exactly align due to the large distance between them, and this is being used to establish a more rigorous positioning of celestial bodies both in and out of the belt, while also deepening our understanding of the universe in general.

Space has always been a field of much interest to mankind, with much more left to be discovered than what has been currently uncovered. In the scientific datea collected up till this point, the Kuiper belt might well be the answer to many of our queries over the physical laws governing astronomical bodies. In a nutshell, the Kuiper belt hosts the farthest objects gravitationally bound to earth. Stretching far from the sun, they were kept under very cold conditions and have not been repeatedly cooled and heated. Hence, holding a very pristine geological and chemical record of the early solar system. Kuiper belt objects which are much shrouded to light, rendering investigation by the Hubble telescope difficult, are antics of the solar system in the form of dark icy bodies. First discovered in 1998, KBOs have deepened our understanding of the solar system. We now know that comets ramify from processes from the Kuiper Belt and that water most probably comes from there too. This holds clues to the origins of life and to the key factors that make planets viable to host life. These discoveries might allow us to accurately pinpoint potential planets, with the adequate characteristics and maybe extend our reach onto extraterrestrial forms of life

The Kuiper belt has, among its revolutionizing discoveries, brought a landmark to the modeling and study of planetary systems and bodies. It has unwound our minds over migration and planetary arrangements: that is over the interactions between astronomical bodies like the sun, and their impact on the orbit of planets, which have changed over time. This has upended fields regarding the evolution of stars and solar systems which are dealt with a completely different approach.

By studying the Kuiper belt, we open the doors to further investigation over the mysteries stretching through space, extending from trans Neptunian bodies, to the possibility of a hypothetical 9th planet.

Contributors:

- Ashvina Caussy ( Lead Author)

- Bradley Virginie

- Hanee Jaufurally

- Jayalakshmee Carroopunnen

- Yash Soobarah

- Nidhi Baindur (Chief Editor)